|

hi all,

just a quick note that in the past months I have been mostly writing on Substack if you are interested in following along, please sign up here: https://marcoaltini.substack.com/ (it’s free) thank you for reading! on January 21st I'll be speaking alongside Keira D'Amato, Ben Rosario, and many others for the Endurance 8020 conference organized by Matt Fitzgerald and Hanna Hunstad

if interested, please see how to register here looking forward to the event, thank you I've enjoyed this chat with Adam, talking about heart rate variability (HRV) outside of sports setting.

We discussed the basics, physiology, technology, stressors, sickness, deep breathing and more. It might be a useful one if you are new to the topic. Thank you for listening This episode of Longevity by Design is an in-depth discussion on heart rate variability (HRV) and the stress response.

We discuss the definition of HRV, how stress impacts the autonomic nervous system, and the many factors that influence HRV. thank you for having me and enjoy. It took a while to learn what works for me in terms of training, rest, and diet, and to better manage stress

I certainly did not expect a 5-year break from racing PRs (nor I expected at this point to break any PR anymore) yet, progress isn’t linear in my latest blog I tried to cover the past 6 months and the changes I implemented: • my training plan and periodization • the tools I built to track progress • how I managed the plan • training intensity distribution • diet and performance thank you for reading More and more wearables have started capturing Heart Rate Variability (HRV) data overnight and combining it with other parameters (e.g. heart rate, sleep data, physical activity) to provide readiness or recovery advice to the user.

Despite some inconsistencies over the past years, as of the end of 2022, Oura, Whoop, and Garmin all work in a very similar way when it comes to HRV measurement. However, the way the data is used in all of these tools when building readiness or recovery scores or when providing advice to the user is often problematic and inconsistent. Naive interpretations (higher is better), lack of a normal range (what’s a meaningful change?), and confounding your physiological response with your behavior, are common issues that limit the utility of data collected with wearables. In my latest blog, I cover data analysis and interpretation to provide you with some useful tips and tools that should allow you to make the most of the collected data and ignore inaccurate interpretations provided by most tools out there. Thank you for reading. I had a nice chat with Charlie about all things heart rate variability (HRV) and running, check it out in this article on Runners World

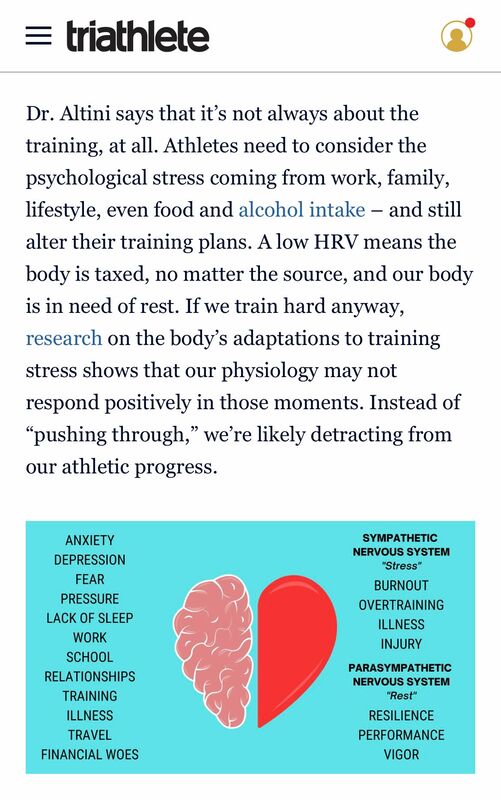

• What's a good HRV? • Factors that affect HRV • What are the benefits of using it to guide training? and more I've enjoyed chatting with Jill about training, psychological stress, and heart rate variability for her latest article in triathlete magazine. Full story here

Thank you for reading Enjoyed chatting with Ross and Mike about the physiology, measurement and application of heart rate variability (HRV) for the latest Real Science of Sport podcast.

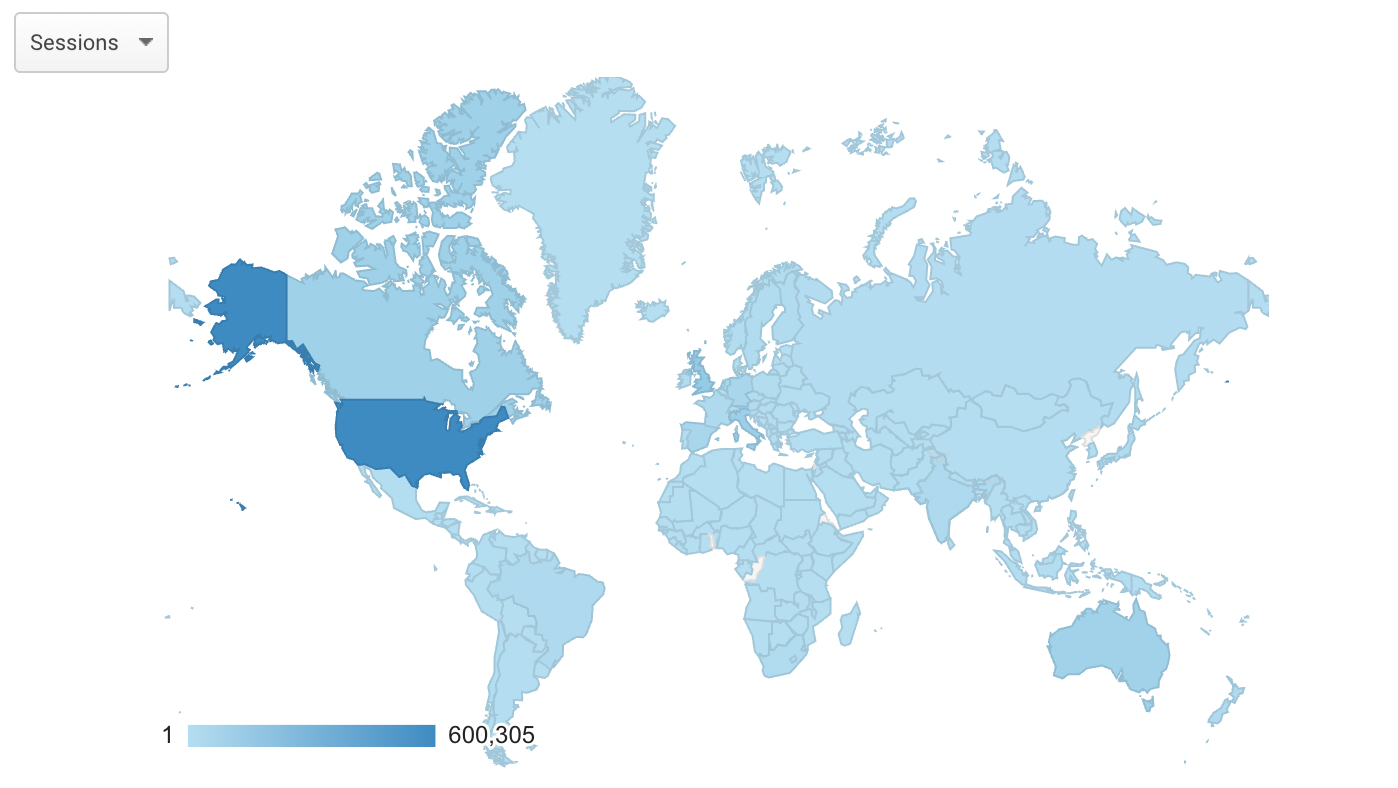

Thank you for having me. You can find it here. 9 years ago I started building HRV4Training, coding the app, and blogging about heart rate variability (HRV)

We somehow managed to do things our way and still put food on the table. About 1 million people ended up on the blog during this period. Grateful for the many relationships this work has led to. Thank you I've enjoyed talking to Jesse and Jeff at The Slow Wave Podcast about all things HRV and sleep

Check it out below video: https://lnkd.in/ez8GcEzT audio: https://lnkd.in/e-mSecV9 Thank you for having me I had a nice chat with Bevan discussing how to collect high quality and meaningful HRV data, how to interpret that data, our latest research with HRV4Training, and more

You can find it at this link, thank you for listening! A few weeks ago I had a nice chat with Jonathan about our work and business @ HRV4Training

If you like building tools, but have no interest in taking over the world, this one is for you :) Episode here, enjoy the listen We have just released the latest version of HRV4Training, which brings a complete re-design of the app

It should be easier now to better understand if your resting physiology is within your normal range That's what matters the most You can find a quick start guide, here You can use HRV4Training either with your phone camera (a method that has been validated and independently validated), or with an Apple Watch, Oura ring, Scosche Rhythm24 or Bluetooth strap All sensing modalities are valid as long as you follow a few simple best practices Thank you for your support Enjoy! About one year ago, following a few interesting exchanges via email with Sander Berk at Dutch Triathlon, as well as with Raúl Celdrán, Alan Couzens and James Cobb on Twitter, I got more interested in HRV analysis during exercise.

Early research from Thomas Gronwald and co-authors had shown that you could potentially identify the aerobic threshold using this method. This looked like a potentially useful way to assess exercise intensity without the need for indirect calorimetry, lactate meters or even knowing our maximal heart rate. A few months later I added DFA alpha 1 to our general purpose research app, the Heart Rate Variability Logger, which became the first tool able to offer this analysis in real-time. I had also released code for others to use, which was indeed picked up by many, developing the various options currently available. The proliferation of these tools, led to many more people trying out the method, more research groups collecting and analyzing data, and more insights on the strengths and limitations of DFA alpha 1. This is exactly how research should work. As scientists, we need to be able to look at the data and the new evidence, and update our view accordingly. Otherwise, we are doing a really poor job. Given the data that I have seen in the past months, both anecdotally from users and in published literature, it is undeniable now that we cannot promote the use of a universal threshold (0.75) to detect the aerobic threshold at the individual level. In this post, I cover in more detail current issues and potential applications of this type of analysis, which certainly remains of interest, even though not for the reasons originally thought. always fun to talk to coaches and athletes that have been using HRV4Training for many years

check out my chat with Colin and Elliot, here Thank you for having me! I've enjoyed being back on the Scientific Triathlon podcast after a few years. In this episode, we discuss:

• HRV basics • our latest research • measurement devices • morning vs night • HRV vs heart rate vs readiness or recovery scores • how to use the data (HRV-guided training, practical tips) and more episode link here, thank you for listening! Grazie Nick for the opportunity to talk about heart rate variability (HRV) and HRV4Training for your latest article

"We take a deep dive into a trendy, but often misunderstood metric in endurance sports" Enjoy the read Recently I have been experimenting more with pre and post-exercise HRV measurements. Below you can find some data and thoughts.

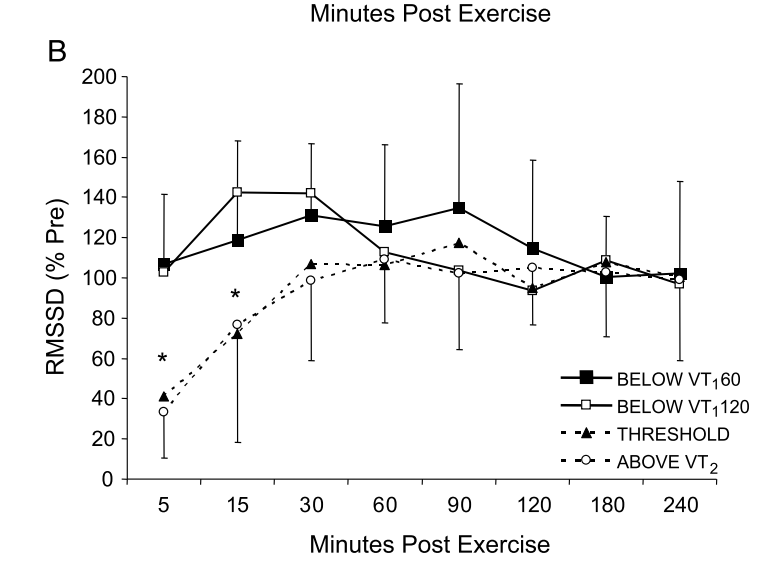

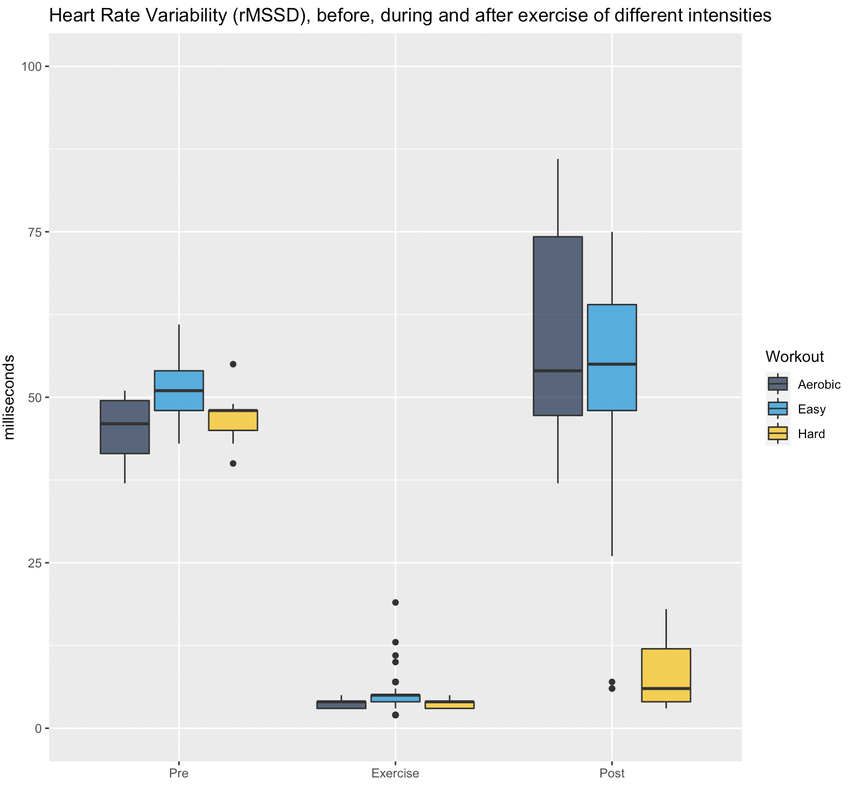

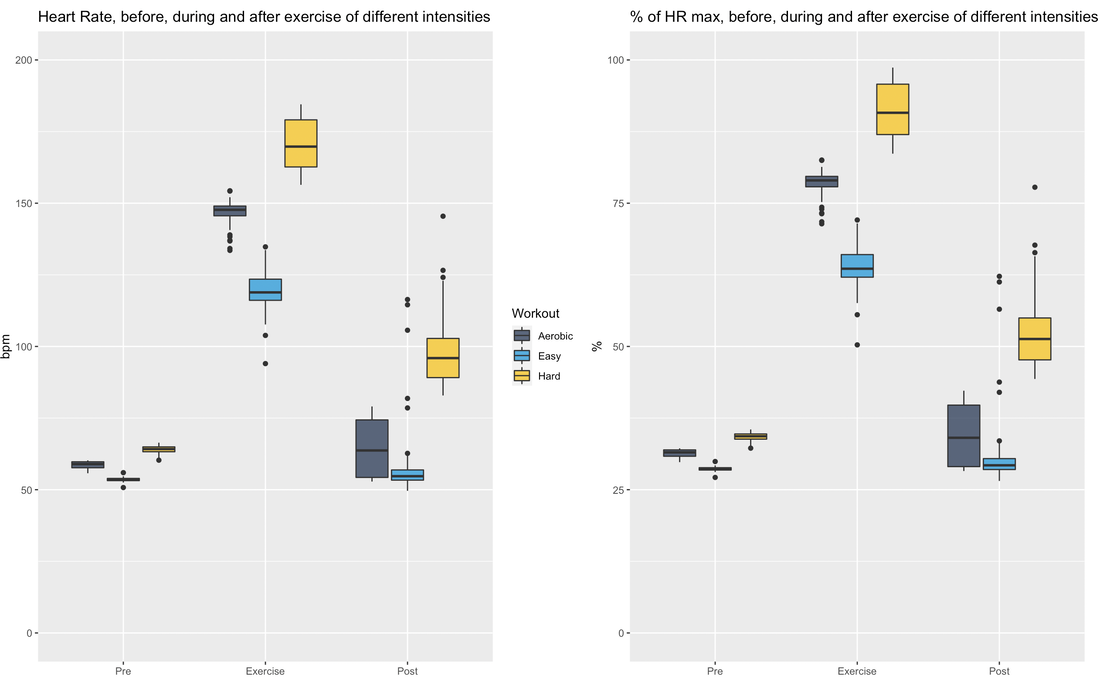

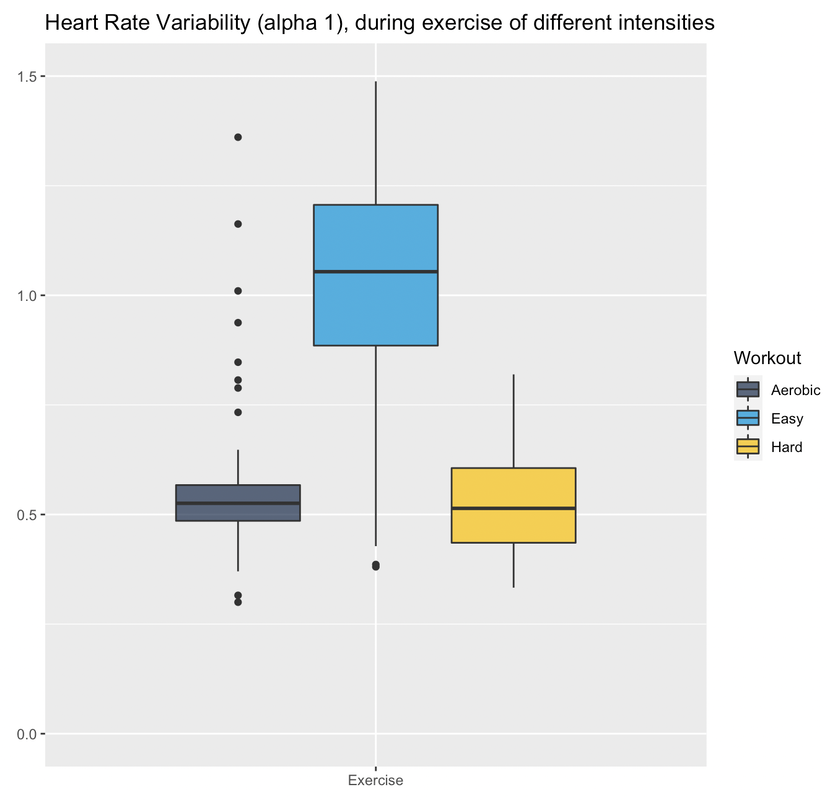

RationaleBased on Stephen Seiler's reasearch, using pre and post-exercise HRV we can better understand the impact of different workouts. By measuring autonomic activity (heart rate, HRV) *immediately* before and after the workout, we isolate the training stressor in a way that allows us to answer different questions, for example, the following come to mind: at what intensity does a workout require a much longer recovery time? (does it need to be hard? what about just a bit harder than "aerobic threshold"?) and what about duration? or type of exercise. In addition, Stephen's research has shown how HRV could increase after easy exercise (below "aerobic threshold"), highlighting important differences between heart rate and HRV in terms of how they reflect autonomic control and recovery. HRV (rMSSD) in the hours after exercise of different intensities. From Seiler, Stephen, Olav Haugen, and Erin Kuffel. "Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: intensity and duration effects." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 39, no. 8 (2007): 1366-1373. ToolsFor the data presented here I used the Heart Rate Variability Logger (that I make: https://hrv.tools) with a Polar H10, but the data from Polar, especially *post* exercise, has been very low quality. Sometimes my heart is to blame, sometimes the sensor. I thought a single long session with the HRV Logger and an H10 was the easiest (no need to start / stop multiple recordings), but the strap gets annoying quickly maybe spot-checks with optical sensors just before and after are better (?) opinions welcome. HEART RATE AND rMSSD PRE, POST, DURINGLet's start with rMSSD, with the caveat that post-exercise, despite very aggressive artifact removal and discarding plenty of data, I still don't trust what I have 100% for some sessions (more data will help). I tagged workouts as easy, aerobic or hard. Aerobic means near aerobic threshold, easy means a lot easier (basically a jog), while hard means VO2max intervals This is just the training that I happened to be doing in the past 7-10 days. Pre-exercise my data was rather similar these days. During exercise, rMSSD is near zero as soon as heart rate > 100 bpm (parasympathetic withdrawal), hence sessions are indistinguishable when using this metric (as expected, this is why it is quite useless to try to determine exercise intensity using rMSSD data collected during exercise). post-exercise, (which is when rMSSD becomes interesting), we have a massive difference between *hard* and everything else. I recall rMSSD was still 4 ms 10 minutes after the session that day. For easy sessions, rMSSD post-exercise is similar or even greater than rMSSD pre-exercise. This is very interesting and also in line with Stephen's findings that I have reported above. Let's look at heart rate now. Below I have plotted the exact same data, changing only the unit, either absolute (beats per minute) or relative to my maximal heart rate (so in percentage). We can see some differences with respect to rMSSD: for easy sessions, HR goes back to pre-training in no time. The spread of the distribution is very narrow post-exercise, which means there is almost no lag in going back to ~50 bpm. During exercise, we have the expected differences in intensity, with heart rate tracking well the type of session. Post-exercise, I normally record for 10-15 minutes (see protocol later), hence the wider the distribution, the more delay for heart rate to re-normalize. It's always interesting to me how the patterns in heart rate and rMSSD can differ, with rMSSD potentially increasing post easy exercise, while heart rate never reducing to pre-exercise levels. Heart rate and rMSSD are not the same. Alpha 1Since I was measuring with the HRV Logger and the Polar H10 (configured with no artifact correction, so basically collecting trash data to be post-processed in R), I could also look into DFA alpha 1. This is relevant only for the exercise part. Alpha 1 looks at the properties of the signal, which are associated with autonomic modulation of heart rhythm, but not specifically to parasympathetic activity and indeed the data covers a broader range and is more useful than rMSSD during exercise. However, as I have noted elsewhere, for me, this metric always provides low values (around 0.5) unless I go extremely easy (definitely easier than "aerobic threshold", whatever that is). See here my lactate data for example. I'll keep looking into this when I use the chest strap, mostly to see if I can find any difference between sessions closer to what I consider my aerobic threshold and harder sessions, or relationships between alpha 1 and post-exercise rMSSD. Food for thought. ProtocolStill going back and forth on some of the details, similarly to the tools section, it's messy. There is unfortunately no way the lab protocols used by Stephen can be replicated in real life (for example, people had to wait for 4 hours post-workout). I started with 10 minutes long measurements pre-exercise, then training and then 30 minutes long measurements post-exercise. This quickly converted into 10' pre and 10-15' post. This means that we can only capture the acute change in the first few minutes, more than the recovery trend, which is a pity, but otherwise unfeasible. I tried to minimize talking and allowed drinking water however, other things mess up the data quickly: swallowing for example, is problematic for HRV. As a result, in the 10-15 minutes of post-exercise data, much of it gets discarded, which is why I grouped the data in pre and post instead of showing any dynamic component in the post-exercise data. Still valuable I believe. For breathing, no control (self-paced). Measuring with the Polar H10 the whole time is easy, but if we were to do spot checks, you could shower and then measure again, instead of e.g. sitting in the living room while being disgusting (also here, opinions are welcome). Wrap-upThis type of data collection is challenging, but despite the limitations and shorter data collections after exercise (with respect to lab studies), I think there is plenty of useful information to investigate if we were to pull it off with a large user-generated study.

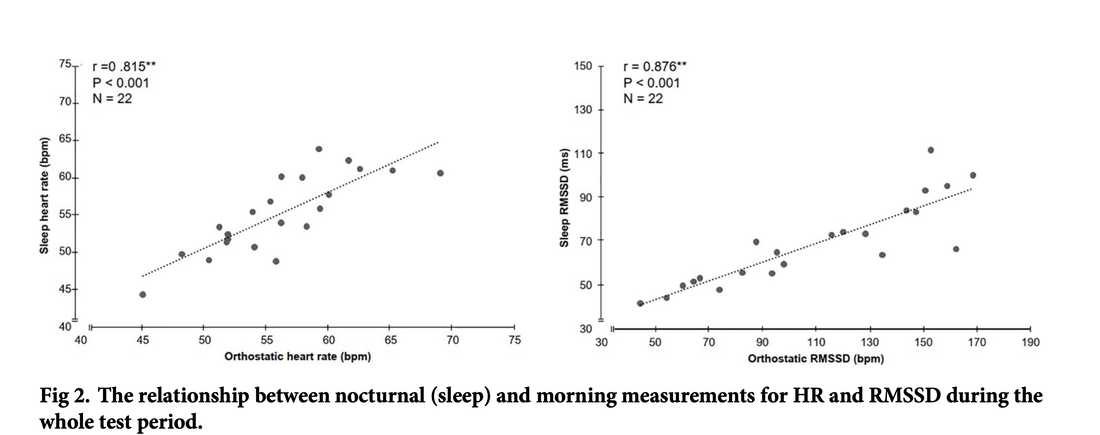

I will collect and think some more. Thank you for reading. Stay in touch. Technology for Heart Rate Variability (HRV) measurement at rest is getting better every day. From our own approach using the phone camera in HRV4Training (validated, and independently validated), to the Oura ring, Polar Vantage V2 and Scosche Rhythm24 (plus of course, good chest straps like Polar H10), it has become really easy to capture high-quality HRV data. In a recent blog, I discussed the importance of using an accurate tool, sampling at the right time, and interpreting your data with respect to your normal values. I have often argued that provided you know what you are doing, morning and night measurements are equivalent in the long run. This does not mean that there are no differences on a daily basis (we'll get to that), but it means that these are both reliable way to assess baseline physiological stress. Check out an example of a few months of my own data, with annotations, here Application of interestWe first need to define our application of interest. Both heart rate and HRV can be used for different applications and measured under different conditions. In this blog, our application of interest is determining chronic physiological stress level, which derives from combined strong acute stressors (e.g. a hard workout, intercontinental travel) and long-lasting chronic stressors (e.g. work-related worries, etc.). By measuring the impact of various stressors (e.g. training or lifestyle) on our resting physiology (HR and HRV), we can make meaningful adjustments that can lead to better health and performance. Latest researchBack to morning vs night. Apart from my anecdotal data above showing a very good match between the two, what does the research say? In the latest paper looking at this exact question, "Evaluation of nocturnal vs. morning measures of heart rate indices in young athletes", Christina Mishica and co-authors report that "heart rate and RMSSD obtained during nocturnal sleep and in the morning did not differ". We can even look at the data for both heart rate and rMSSD, a marker of parasympathetic activity (the same feature used in HRV4Training or in the Oura ring), which indeed show great agreement: You can find the full text of the paper here. Important differencesAs I have tried to cover in this and other blog posts, morning and night measurements can be used to capture baseline physiological stress in response to acute and chronic stressors. Both methods have been used in different studies resulting in the same outcomes in terms of the relationship between HRV, training load, and recovery (see an overview here). While long term trends will be similar between these two methods, there are a few differences to keep in mind, mainly linked to these aspects:

Practical takeawaysWhat are the takeaways here?

In my opinion, when it comes to the data, there is no advantage in using one method or the other. However, if you prefer to wear something over the night, get a device that does so. If you prefer not to wear something during the night and just to take a measurement in the morning, then go that way. If your athlete can’t be bothered to take a morning measurement, get a device that tracks HRV during the night. If you are not sure this is for you, you can use your phone camera and invest as little as 10$ in measuring your physiology daily with an independently validated HRV app such as HRV4Training. Once again, if you like wearables, they can clearly capture high-quality HRV data as we sleep. Just make sure to use one that gives you the full night of data, as otherwise HRV measurements won't be reliable (as I discuss in greater detail here). My recommendation would be the Oura ring for this exact reason: most other sensors will provide automatically collected sporadic data points (e.g. 5 minutes during the night, like the Apple Watch does), which unfortunately are noisy and do not reflect underlying physiological stress very well. As an alternative, you can get the same data with a morning measurement taken with HRV4Training, the only validated camera-based app. Pretty simple and cost effective, as long as measuring in the morning works in your daily routine. This is great news as we all have different reasons to use one method or the other (cost, preference for passive measurements, etc.), but as long as we use valid tools, the same physiological processes can be captured over time. This consistency will help us move forward in many areas of research in which these sensors or apps are currently deployed. Stay in touch. |

Marco ALtiniFounder of HRV4Training, Advisor @Oura , Guest Lecturer @VUamsterdam , Editor @ieeepervasive. PhD Data Science, 2x MSc: Sport Science, Computer Science Engineering. Runner Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed