|

In this post, I look at the long-term effects of deep breathing on heart rate variability (HRV) as measured during deep breathing practice

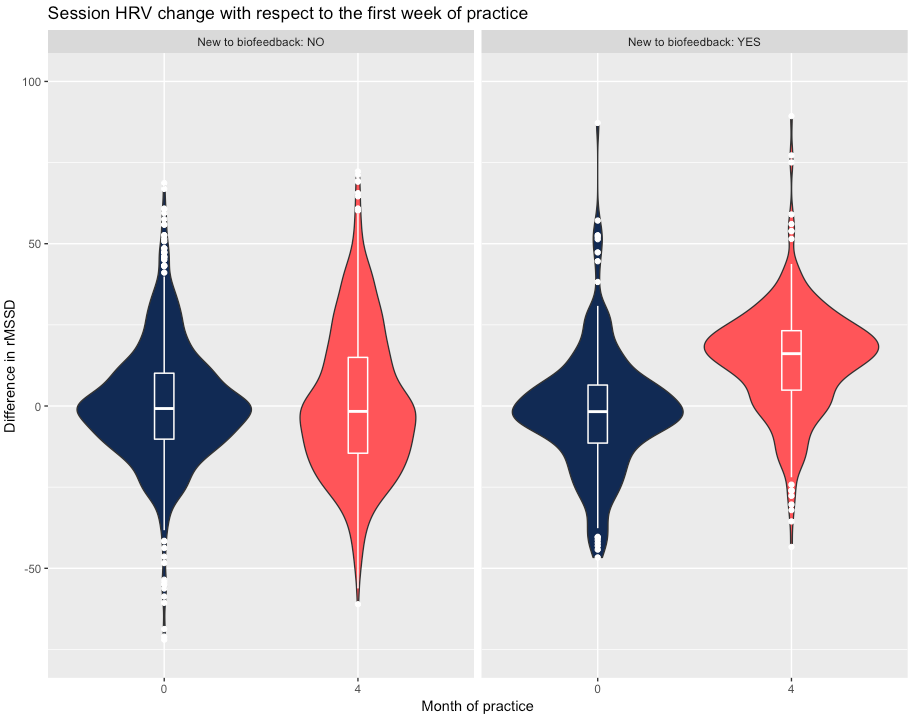

While there is plenty of data and published literature on the acute effect of deep breathing on HRV (basically the difference between resting conditions and practice), we know much less about long-term effects. Looking at this data might help us better understand the relationship between deep breathing and long-term physiological changes (if any!) Enjoy the read In the past few months, I've talked a lot about HRV during exercise. If this is new to you, head over to this blog post for an overview. In this post, I'd like to discuss potential issues with estimating heart rate (HR) from HRV data. And in particular, if it makes sense to do so. Why is this important? The DFA-based method for exercise intensity assessment discussed in the blogs linked above, could be used to determine at what heart rate DFA alpha 1 crosses 0.75. It is of course very practical to do so. We might not always be able to check DFA alpha 1, similarly to ventilatory or lactate thresholds, so we look at heart rate in relation to those crossing points, to use heart rate for real time guidance or training zones definition during following workouts. However, heart rate and HRV carry different information. This is rather obvious, for example resting HR changes with fitness, while HRV less so. Similarly, HRV is tightly coupled to stress responses and more sensitive to stressors, with respect to HR. Depending on context, the relationship between HR and HRV might even be the opposite of the typical increase in HR associated with a decrease in HRV. For example, during deep breathing average HR tends to increase a bit, while HRV shoots up, therefore both increasing with respect to resting conditions. Example of increased HR and HRV during deep breathing (right) with respect to resting conditions (left). Deep breathing was carried out at 5.5 breaths/minute, while you can count about 9.5 breathing cycles in the 55 seconds recorded for the resting measurement. This is quite typical and differs from the expected relationship between HR and HRV, which normally go in opposite directions. Context matters. Curtesy of HRV4Biofeedback Back to exercise HR and HRV now. If HR and HRV carry different information (which is the whole point of using HRV and not just HR), then does it make sense to use HRV just to estimate HR? We can also translate this to morning measurements: would you use your morning HRV just to determine what's your HR when you are well recovered? I wouldn't, because once again, they carry different information and determining what's a good HR based on HRV, would not provide the same level of information (because HRV can differ at the same HR). So shall we fit a regression model or just look at the data to determine at what HR we cross DFA alpha 1 at 0.75, so that we can determine our "aerobic threshold heart rate"? Maybe. Or maybe not. If we think that this approach is solid, maybe we should just use DFA alpha 1 to determine exercise intensity, no matter the heart rate. Forgetting about the issue of being able to practically do so, would that be a better way to use the data? Obviously within individuals the relationship between HR and DFA alpha 1 at 0.75 won't differ too much on a day to day basis unless fitness or environmental factors change. So we might also get away with the more standard approach of using DFA alpha 1-derived HR, but the issue I want to highlight here is more theoretical on the validity of using this approach. These issues are exemplified by the difference that seems to be present between how HR and DFA alpha 1 behave in the context of longer efforts with cardiac decoupling. Below you can see my data on a day which shows large cardiac decoupling and no change in alpha 1 (same external load during the workout). Similarly, Bruce has shown that cardiac decoupling does not seem to affect alpha 1. While we do not have the full picture on this, it seems clear that the two signals once again carry different information, and maybe we should not just use one, to estimate the other. Example of increased HR due to cardiac drift (warmer day), without a drop in alpha 1. Similar external load (pace) across this run. Courtesy of the HRV Logger The bottom line here is that in my opinion, while it is practical to use "methods able to identify the aerobic threshold" to determine at what heart rate that threshold is, using these instruments with the only purpose of determining the heart rate threshold might be a flawed approach or simply do not provide the full picture on underlying physiological responses.

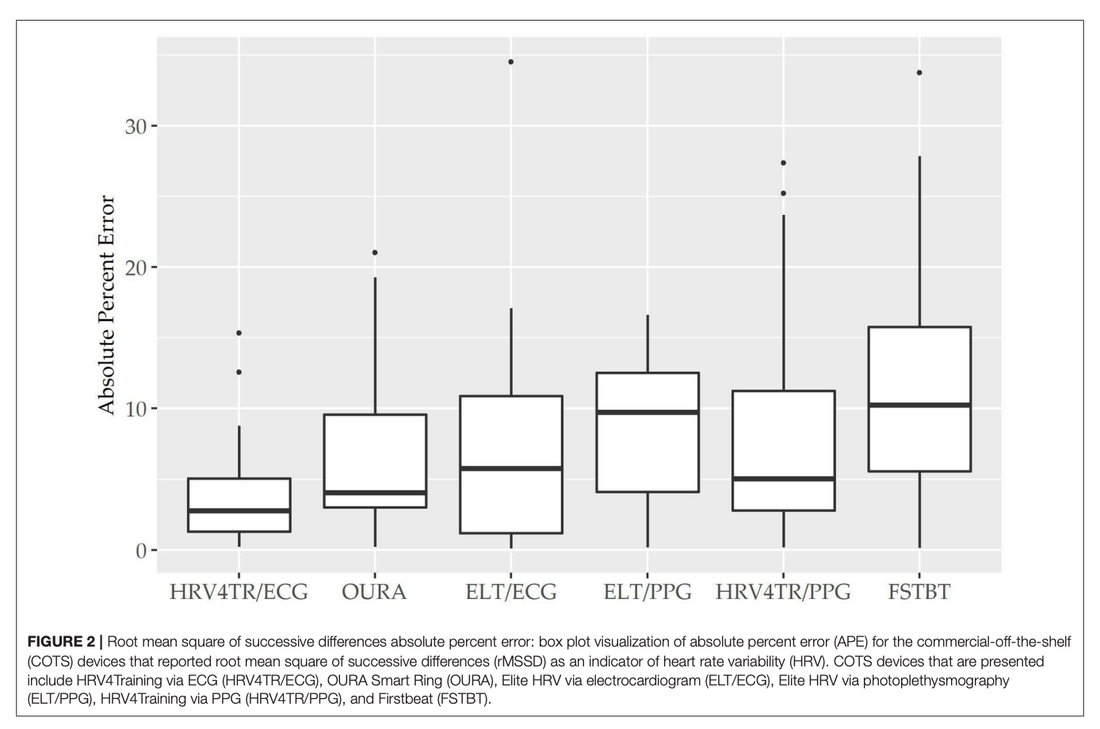

If DFA alpha 1 confirms to be a valid approach, maybe it is simply another parameter we can use to assess training intensity, based on its own value, and not necessarily its relationship with heart rate. There's a new independent validation out looking at the accuracy of commercially available HRV apps and sensors

Great to see the results for the lowest median error:

This is confirmation of the quality of the work we have been doing for the past 8 years, starting with early analysis of the accuracy, then our validation paper, and finally with this independently run study confirming the accuracy of the methods we have developed for both the camera based acquisition and artifact removal for RR intervals acquired from external sensors Some thoughts at this link |

Marco ALtiniFounder of HRV4Training, Advisor @Oura , Guest Lecturer @VUamsterdam , Editor @ieeepervasive. PhD Data Science, 2x MSc: Sport Science, Computer Science Engineering. Runner Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed