|

Recently I have been experimenting more with pre and post-exercise HRV measurements. Below you can find some data and thoughts.

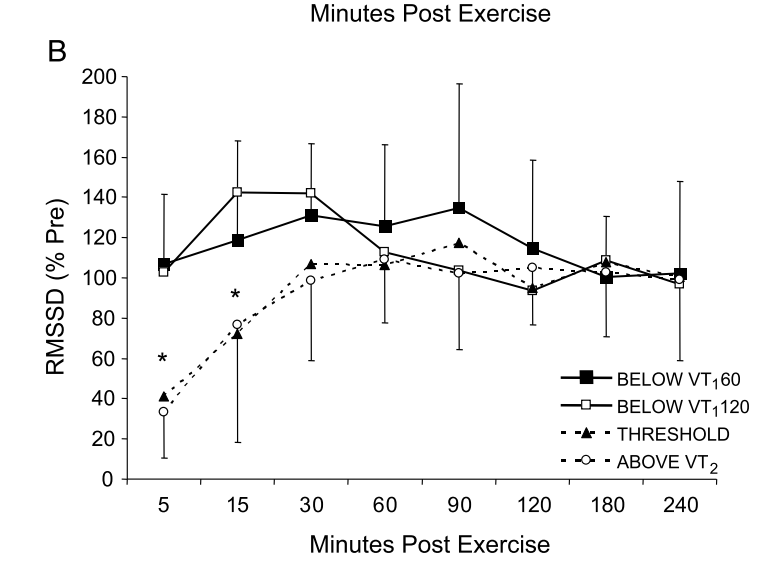

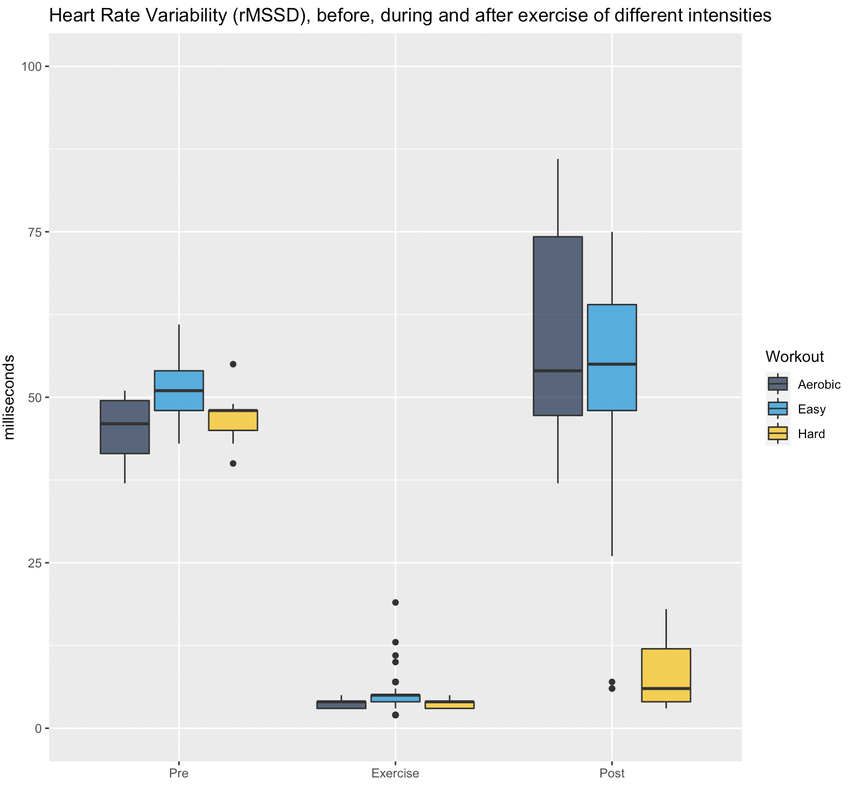

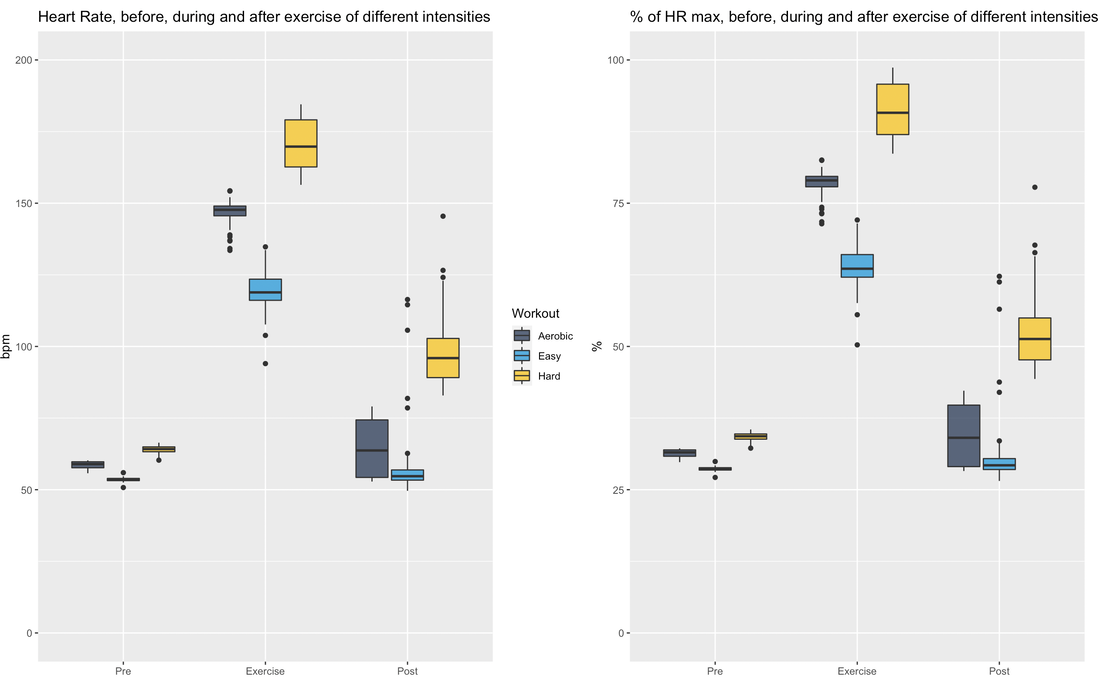

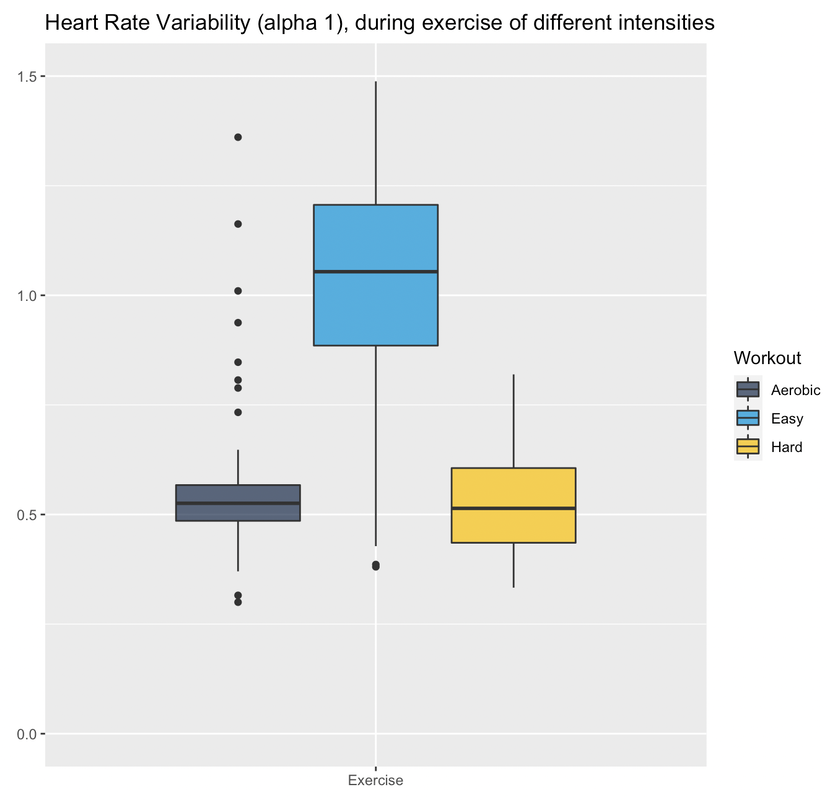

RationaleBased on Stephen Seiler's reasearch, using pre and post-exercise HRV we can better understand the impact of different workouts. By measuring autonomic activity (heart rate, HRV) *immediately* before and after the workout, we isolate the training stressor in a way that allows us to answer different questions, for example, the following come to mind: at what intensity does a workout require a much longer recovery time? (does it need to be hard? what about just a bit harder than "aerobic threshold"?) and what about duration? or type of exercise. In addition, Stephen's research has shown how HRV could increase after easy exercise (below "aerobic threshold"), highlighting important differences between heart rate and HRV in terms of how they reflect autonomic control and recovery. HRV (rMSSD) in the hours after exercise of different intensities. From Seiler, Stephen, Olav Haugen, and Erin Kuffel. "Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: intensity and duration effects." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 39, no. 8 (2007): 1366-1373. ToolsFor the data presented here I used the Heart Rate Variability Logger (that I make: https://hrv.tools) with a Polar H10, but the data from Polar, especially *post* exercise, has been very low quality. Sometimes my heart is to blame, sometimes the sensor. I thought a single long session with the HRV Logger and an H10 was the easiest (no need to start / stop multiple recordings), but the strap gets annoying quickly maybe spot-checks with optical sensors just before and after are better (?) opinions welcome. HEART RATE AND rMSSD PRE, POST, DURINGLet's start with rMSSD, with the caveat that post-exercise, despite very aggressive artifact removal and discarding plenty of data, I still don't trust what I have 100% for some sessions (more data will help). I tagged workouts as easy, aerobic or hard. Aerobic means near aerobic threshold, easy means a lot easier (basically a jog), while hard means VO2max intervals This is just the training that I happened to be doing in the past 7-10 days. Pre-exercise my data was rather similar these days. During exercise, rMSSD is near zero as soon as heart rate > 100 bpm (parasympathetic withdrawal), hence sessions are indistinguishable when using this metric (as expected, this is why it is quite useless to try to determine exercise intensity using rMSSD data collected during exercise). post-exercise, (which is when rMSSD becomes interesting), we have a massive difference between *hard* and everything else. I recall rMSSD was still 4 ms 10 minutes after the session that day. For easy sessions, rMSSD post-exercise is similar or even greater than rMSSD pre-exercise. This is very interesting and also in line with Stephen's findings that I have reported above. Let's look at heart rate now. Below I have plotted the exact same data, changing only the unit, either absolute (beats per minute) or relative to my maximal heart rate (so in percentage). We can see some differences with respect to rMSSD: for easy sessions, HR goes back to pre-training in no time. The spread of the distribution is very narrow post-exercise, which means there is almost no lag in going back to ~50 bpm. During exercise, we have the expected differences in intensity, with heart rate tracking well the type of session. Post-exercise, I normally record for 10-15 minutes (see protocol later), hence the wider the distribution, the more delay for heart rate to re-normalize. It's always interesting to me how the patterns in heart rate and rMSSD can differ, with rMSSD potentially increasing post easy exercise, while heart rate never reducing to pre-exercise levels. Heart rate and rMSSD are not the same. Alpha 1Since I was measuring with the HRV Logger and the Polar H10 (configured with no artifact correction, so basically collecting trash data to be post-processed in R), I could also look into DFA alpha 1. This is relevant only for the exercise part. Alpha 1 looks at the properties of the signal, which are associated with autonomic modulation of heart rhythm, but not specifically to parasympathetic activity and indeed the data covers a broader range and is more useful than rMSSD during exercise. However, as I have noted elsewhere, for me, this metric always provides low values (around 0.5) unless I go extremely easy (definitely easier than "aerobic threshold", whatever that is). See here my lactate data for example. I'll keep looking into this when I use the chest strap, mostly to see if I can find any difference between sessions closer to what I consider my aerobic threshold and harder sessions, or relationships between alpha 1 and post-exercise rMSSD. Food for thought. ProtocolStill going back and forth on some of the details, similarly to the tools section, it's messy. There is unfortunately no way the lab protocols used by Stephen can be replicated in real life (for example, people had to wait for 4 hours post-workout). I started with 10 minutes long measurements pre-exercise, then training and then 30 minutes long measurements post-exercise. This quickly converted into 10' pre and 10-15' post. This means that we can only capture the acute change in the first few minutes, more than the recovery trend, which is a pity, but otherwise unfeasible. I tried to minimize talking and allowed drinking water however, other things mess up the data quickly: swallowing for example, is problematic for HRV. As a result, in the 10-15 minutes of post-exercise data, much of it gets discarded, which is why I grouped the data in pre and post instead of showing any dynamic component in the post-exercise data. Still valuable I believe. For breathing, no control (self-paced). Measuring with the Polar H10 the whole time is easy, but if we were to do spot checks, you could shower and then measure again, instead of e.g. sitting in the living room while being disgusting (also here, opinions are welcome). Wrap-upThis type of data collection is challenging, but despite the limitations and shorter data collections after exercise (with respect to lab studies), I think there is plenty of useful information to investigate if we were to pull it off with a large user-generated study.

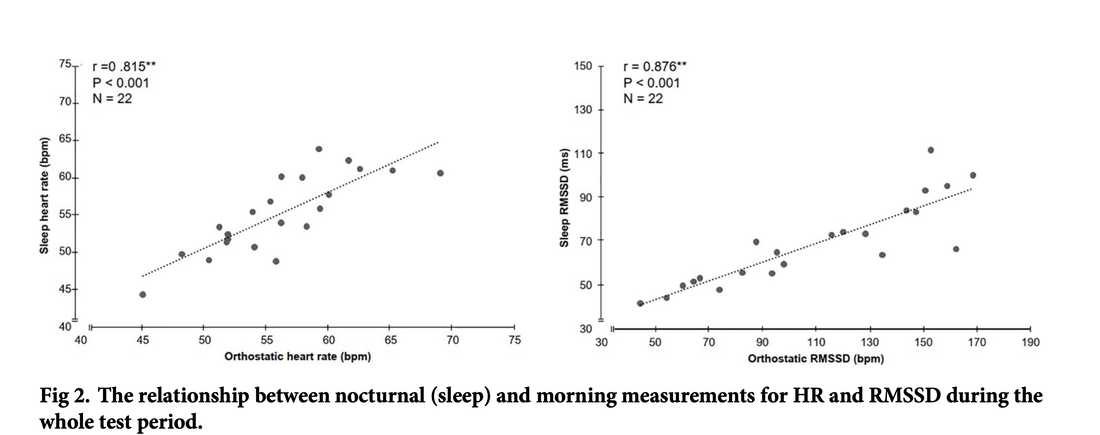

I will collect and think some more. Thank you for reading. Stay in touch. Technology for Heart Rate Variability (HRV) measurement at rest is getting better every day. From our own approach using the phone camera in HRV4Training (validated, and independently validated), to the Oura ring, Polar Vantage V2 and Scosche Rhythm24 (plus of course, good chest straps like Polar H10), it has become really easy to capture high-quality HRV data. In a recent blog, I discussed the importance of using an accurate tool, sampling at the right time, and interpreting your data with respect to your normal values. I have often argued that provided you know what you are doing, morning and night measurements are equivalent in the long run. This does not mean that there are no differences on a daily basis (we'll get to that), but it means that these are both reliable way to assess baseline physiological stress. Check out an example of a few months of my own data, with annotations, here Application of interestWe first need to define our application of interest. Both heart rate and HRV can be used for different applications and measured under different conditions. In this blog, our application of interest is determining chronic physiological stress level, which derives from combined strong acute stressors (e.g. a hard workout, intercontinental travel) and long-lasting chronic stressors (e.g. work-related worries, etc.). By measuring the impact of various stressors (e.g. training or lifestyle) on our resting physiology (HR and HRV), we can make meaningful adjustments that can lead to better health and performance. Latest researchBack to morning vs night. Apart from my anecdotal data above showing a very good match between the two, what does the research say? In the latest paper looking at this exact question, "Evaluation of nocturnal vs. morning measures of heart rate indices in young athletes", Christina Mishica and co-authors report that "heart rate and RMSSD obtained during nocturnal sleep and in the morning did not differ". We can even look at the data for both heart rate and rMSSD, a marker of parasympathetic activity (the same feature used in HRV4Training or in the Oura ring), which indeed show great agreement: You can find the full text of the paper here. Important differencesAs I have tried to cover in this and other blog posts, morning and night measurements can be used to capture baseline physiological stress in response to acute and chronic stressors. Both methods have been used in different studies resulting in the same outcomes in terms of the relationship between HRV, training load, and recovery (see an overview here). While long term trends will be similar between these two methods, there are a few differences to keep in mind, mainly linked to these aspects:

Practical takeawaysWhat are the takeaways here?

In my opinion, when it comes to the data, there is no advantage in using one method or the other. However, if you prefer to wear something over the night, get a device that does so. If you prefer not to wear something during the night and just to take a measurement in the morning, then go that way. If your athlete can’t be bothered to take a morning measurement, get a device that tracks HRV during the night. If you are not sure this is for you, you can use your phone camera and invest as little as 10$ in measuring your physiology daily with an independently validated HRV app such as HRV4Training. Once again, if you like wearables, they can clearly capture high-quality HRV data as we sleep. Just make sure to use one that gives you the full night of data, as otherwise HRV measurements won't be reliable (as I discuss in greater detail here). My recommendation would be the Oura ring for this exact reason: most other sensors will provide automatically collected sporadic data points (e.g. 5 minutes during the night, like the Apple Watch does), which unfortunately are noisy and do not reflect underlying physiological stress very well. As an alternative, you can get the same data with a morning measurement taken with HRV4Training, the only validated camera-based app. Pretty simple and cost effective, as long as measuring in the morning works in your daily routine. This is great news as we all have different reasons to use one method or the other (cost, preference for passive measurements, etc.), but as long as we use valid tools, the same physiological processes can be captured over time. This consistency will help us move forward in many areas of research in which these sensors or apps are currently deployed. Stay in touch. |

Marco ALtiniFounder of HRV4Training, Advisor @Oura , Guest Lecturer @VUamsterdam , Editor @ieeepervasive. PhD Data Science, 2x MSc: Sport Science, Computer Science Engineering. Runner Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed